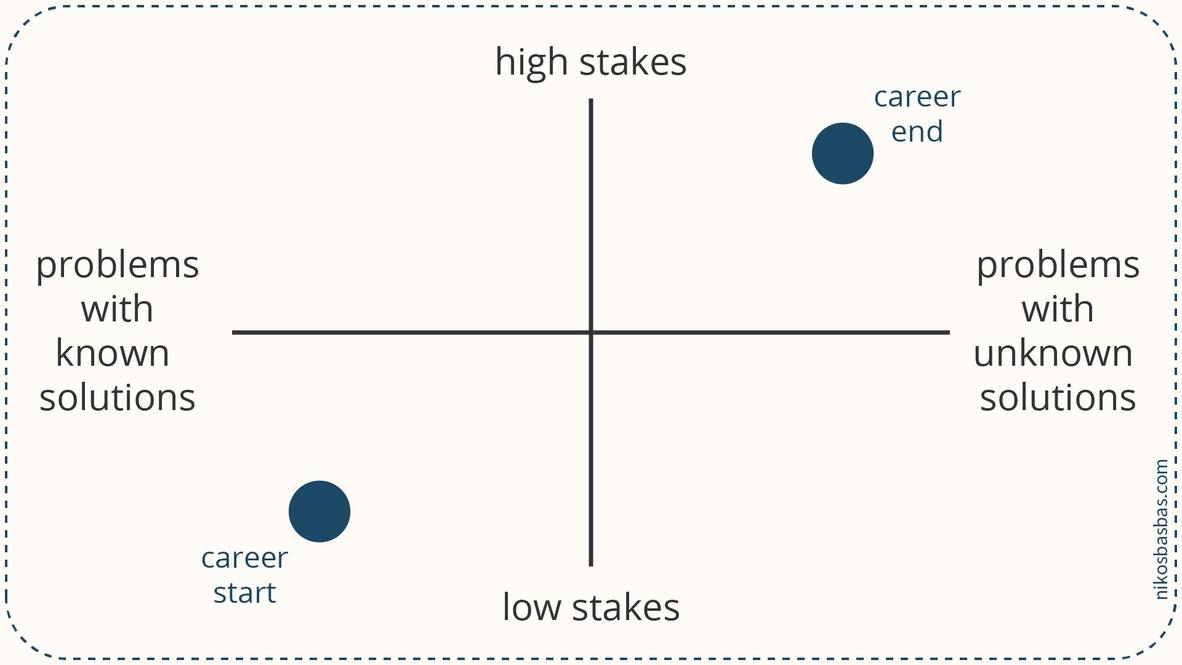

Let's talk about career developments for a moment. Many people's first job consists of unimportant, boring tasks that no one else in the organisation wants to do. On the other hand, the last job before retirement, when one has amassed a ton of experience, may involve tackling novel and important problems.

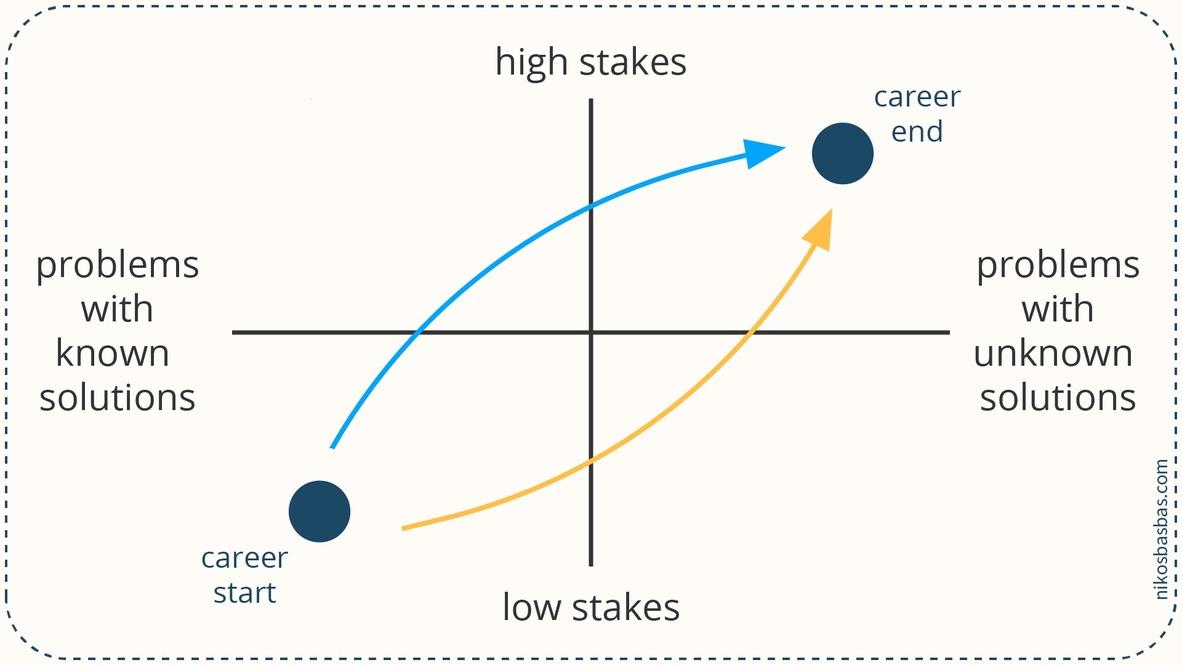

Practically everyone starts out in the bottom left quadrant because people in their twenties suck, professionally speaking. Pretty soon after, however, they start moving to the top right quadrant. There is an infinite number of ways how to get there, but I think they cluster around two distinct trajectories:

Eye doctors, for example, follow the blue trajectory. After a few months of greeting patients and drafting diagnoses they get more responsibility and may start performing simple medical interventions, like fishing out a splinter out of a patient's eye. Their new tasks remain routine, meaning they have been solved a gazillion times before, and the young doctor's job is to follow the tried and tested procedure. However, the consequences of making a mistake become higher. Push a scalpel a little further, and a patient may lose an eye.

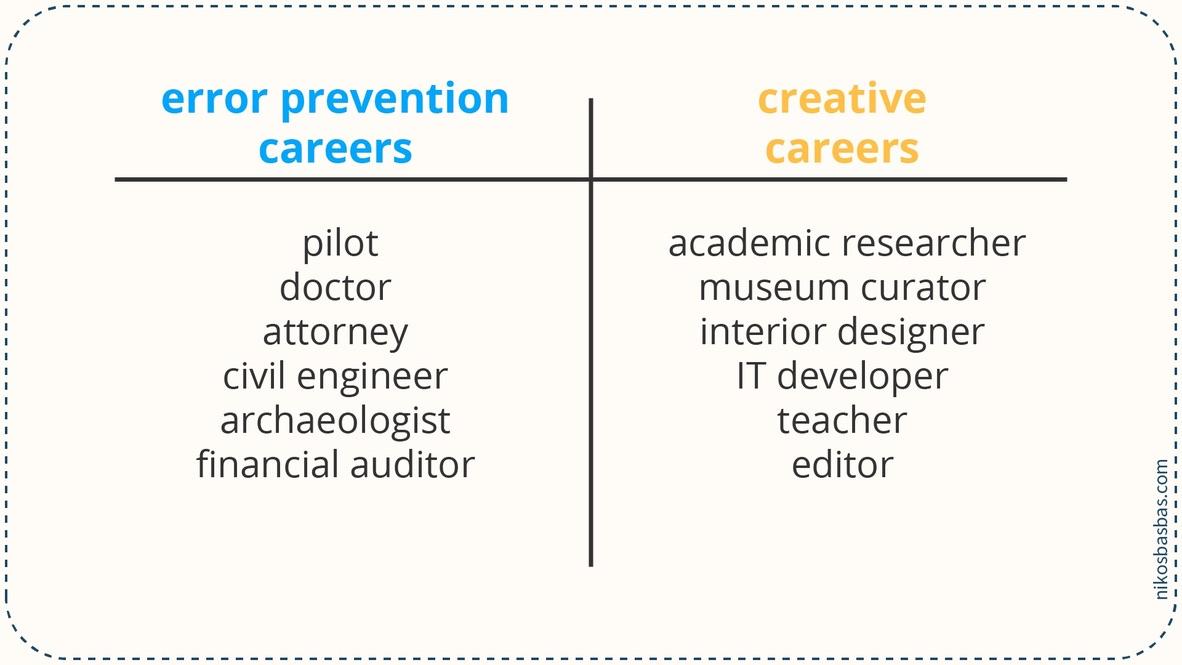

The defining characteristic of blue careers is error prevention. Professionals in fields such as medicine, archaeology, civil engineering, law, or finance may cause a human, environmental, humanitarian, or cultural disasters if they err. It is therefore not surprising they try to minimise the risk of an error, often by being highly methodical in their work and following standard operating procedures.

Most careers, however, follow the yellow trajectory. Relatively very little damage results from an academic researcher making a mistake. This is not to say yellow careers are unimportant, on the contrary. By channelling their creativity, designers, inventors, and artists occasionally drive human progress by leaps and bounds.

This week's rant is this: The way we teach in (higher) education prepares students well for blue careers but are unsuitable for the yellow ones. Rigid programme curricula, domain-based instruction, summative assessment, and credentials are necessary in high-stakes fields, but may stand in the way of developing creative professionals.

A good start for designing education for creatives may be flipping the current system on its head. Get rid of prescribed curricula and allow students to take courses from various disciplines. Do not insist on program completion. Base your courses on challenges or problems, not on domains. Teach skills relevant for problem solving, such as design thinking, research, and collaboration. Focus on formative assessment. Teach questions no one knows answers to. Make students build portfolios.

As we improve systems and technologies for automating tasks and eliminating human errors, more people will have an opportunity to work on novel, interesting problems, and our educational systems should adapt.