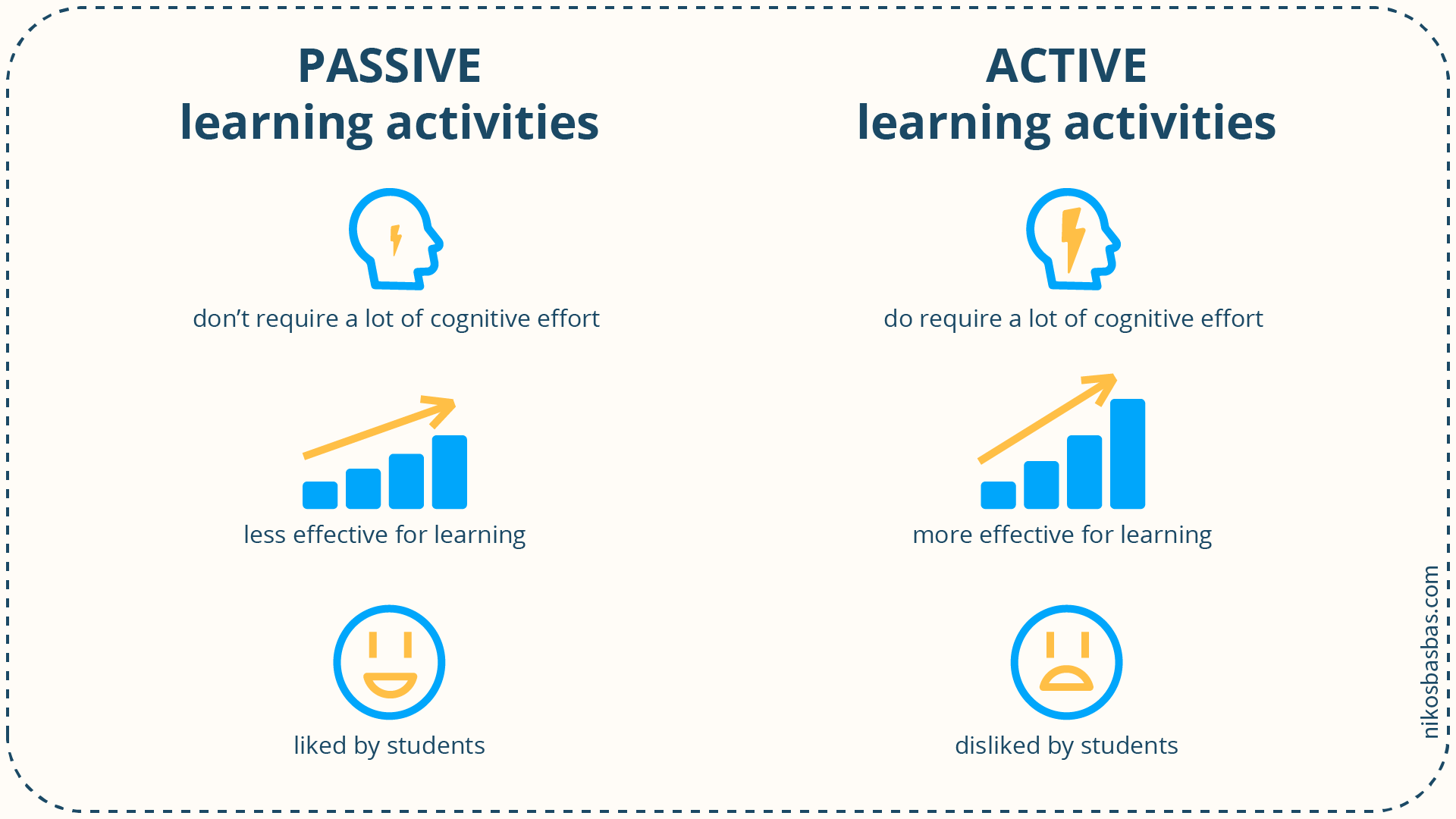

Every bit of research tells us active learning activities, colloquially known as learning by doing*, are better than passive learning activities. I define an active learning activity as an activity that requires a learner to spend a significant amount of mental effort in order to complete it, for example, a well-moderated discussion, a thought-provoking quiz, or an interesting project. A passive learning activity, on the other hand, does not require a big investment of cognitive resources. A lecture entirely delivered by a professor allows students to sit through it without firing a single neuron.

But here's the kicker: Despite the overwhelming evidence that active learning activities are lit, people hate them. I call this the active learning sucks fallacy, and believe it explains why many courses fail to engage students despite being designed according to best active learning principles. The good news is there are a few relatively simple things the course team can do to make students not hate, and maybe even like, active learning.

Why do people suffer from the active learning sucks fallacy?

For two reasons. First, people genuinely believe they learn less from active learning activities than from passive ones. Why? Because, let's face it, we are like Jon Snow:

Most of us don't really know how learning works, and assess instructional effectiveness using instinct. But instinct is a fickle thing, and may have us pay attention to things that don't really matter, and overlook things that do.

What doesn't really matter, but we think it does: Flow of class.

An active class may feel like an anarchist convention. There is a lot of jumping from activity to activity, no one seems to be in control of the situation, and conversations are all over the place and full of errors. In contrast, a passive lecture can be a neat little event, especially when delivered by a great speaker. It can feel very satisfying to sit in a familiar seat and listen to a coherent, uninterrupted story. But class neatness and flow may create an illusion of learning - the fact that a lecturer speaks fluently on a topic doesn't mean students can.

What matters, but we underestimate it: Effort.

Learning something new is like getting physically fit - it takes effort and there are no shortcuts. Active learning activities are designed to put our brains to work, and that is why they are effective. However, if we don't know that effort is good for us, we may mistakenly take it for a sign of poor learning.

The second reason why we tend to dislike active learning activities is that they often involve asking questions, formulating arguments, and articulating deeply held beliefs in front of others, which can be quite an unnerving experience for the shy and insecure among us. After all, we are social creatures mostly living in meritocratic societies where status is determined in large part by competence, so it doesn't come as a surprise we do not jump at the idea of accidentally ridiculing ourselves during a stupid "active learning activity".

How to help students overcome the active learning sucks fallacy?

Start by setting the stage for active learning, especially when students are new to it. Consider including cues about the course format already during its promotion. Akimbo, an online course provider, spend half of their 30 second ad saying things like "[The course] works, if you do the work" and "[The course] is not a bunch of videos, it's a workshop". At the beginning of a course, take time to clearly explain the level of engagement and commitment you expect. Then, educate students that class fluency doesn't matter nearly as much as mental effort. Set house rules that help create a safe learning environment. And finally, listen to students' concerns throughout the course and address them.

Conclusion

Active learning activities are great for learning, but may not feel that way. Therefore it is not enough to merely embed them in a course; it takes a bit of explaining and expectation management for students to embrace them, especially when they are not used to this form of instruction.

Notes

*Learning by doing is not exactly the same as active learning. One can be straining their brain ("learning actively") without moving a finger, that is without doing. However, for the purposes of this post we will neglect the differences between the terms.

Sources

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251-19257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116